Dark Age Scholastics and Nuclear Energy Theatrics

How The Irish Can Save Civilization Again, Part 2

NOTE: While Part 2 of a series (see Part 1 here), this essay could be read independently if you were only interested in learning about nuclear energy and the wider energy situation we are in. My aim here was to be quite comprehensive and provide, at minimum, a curated collation of resources that could guide further reading. Moreover, this topic simply deserves serious and careful attention. -----------

After an honest analysis of best available evidence, the coming years will likely see two patterns of travel for the European West. Both of which, to put it mildly, are rather unfavourable.

On the one hand, we could see an unravelling of large chunks of European society into gritty carnage due to years of grossly incompetent and apathic leadership by the Rulers leading to predictable increases in social unrest and violence. This is especially likely if nuclear war blackens the skies and causes food shortages. Or even if non-nuclear war escalates around Ukraine such that global supply chains are yet more seriously disrupted causing further deprivation and migrant crises. Then what happens if communications satellites start getting destroyed? Or if underwater internet cables start getting cut? "Ninety-five per cent of the world’s internet traffic”, wrote Alexander Downer in the Spectator, “passes through just 200 undersea fibre-optic cable systems."

On the other hand, we could see the accelerated spread of Chinese Communist Party style techno-tyrannical dystopia. This would be a centrally controlled state/neo-feudal apparatus with vastly invasive surveillance as well as creepy control structures such as digital currency and social credit systems. The bloodied and starving chaos described above may even create the ideal conditions for sliding into this second possibility. While to some this may sound farfetched, it is an all-too-real possibility. We did, after all, rather meekly allow ourselves to be ‘locked-down’ for months in the face of a virus that killed much closer to 0.1 than 1% of those infected. As such, what would our fragmented and safety obsessed society play along with in the face of nuclear war induced food shortages, or an engineered virus with an infection fatality rate of 60% being released by another accidental lab leak, or any number of other pathogens being released by terrorists with access to exponentially powerful biotech?

This isn’t the first time Western civilization was under threat though. And, if one takes Thomas Cahill seriously in his 1995 book, How the Irish Saved Civilization, Ireland may well have played a key role in saving it once before.

Cahill’s central thesis is that Irish monks, apart from setting sail as “white martyrs” to establish monasteries and spread Christianity all over Europe, played a central role in keeping the flame of scholarly learning alight during a period of intellectual recession in Europe after the Western Roman empire finally collapsed:

“Wherever they went the Irish brought with them their books, many unseen in Europe for centuries…Wherever they went they brought their love of learning and their skills in book making. In the bays and valleys of their exile, they reestablished literacy and breathed new life into the exhausted literary culture of Europe…And that is how the Irish saved civilization.” (pg. 196)

“Nowhere else in the Christian West”, wrote historian Tom Holland in Dominion, “were saints quite as tough, quite as holy, as they were in Ireland.” (pg. 156) Moreover, these saints and scholars spread learning not only through Christian writings, but also through “pagan” texts alongside driving innovations in vernacular literacy. Cahill writes:

“Latin literature would almost surely have been lost without the Irish, and illiterate Europe would hardly have developed its great national literatures without the example of Irish, the first vernacular literature written down. Beyond that, there would have perished in the west not only literacy but all the habits of mind that encourage thought. … “The weight of the Irish influence on the continent,” admits James Westfall Thompson, “is incalculable.”” (pg. 193-194)

The opening chapter of Cahill’s book begins in the early 5th century just as the Western Roman empire is entering its closing decades and the Dark Ages were beginning. “On the last, cold day of December in the dying year we count as 406,” writes Cahill, “the river Rhine froze solid, providing the natural bridge that hundreds of thousands of hungry men, women, and children had been waiting for.” (pg. 11) This matted multitude were known as the “barbari” to the complacently dominant Romans, and were not seen as a genuine threat. After all, that “Rome should ever fall was unthinkable to Romans: its foundations were unassailable, sturdily sunk in a storied past and steadily built on for eleven centuries and more.” (pg. 12) By 410, however, the barbari will have sacked Rome and marked the beginning of the end for the western empire whose last emperor will die in 476. To be crystal clear, I highlight this event not to make some thinly veiled xenophobic comment on immigration. No, I do so in order to point out that civilizations have collapsed in the past in ways that were unexpected by those who lived in them. In fact, the most obvious thing about all prior civilizations, is that they no longer exist. As such, what makes us so certain that our civilization will endure? In an April 2022 piece for Tablet Magazine, Ugo Barbi wrote:

“Ruin, which we may also call “collapse,” is a feature of our world. We experience it with our health, our job, our family, our investments. We know that when ruin comes, it is unpredictable, rapid, destructive, and spectacular. And it seems to be impossible to stop until everything that can be destroyed is destroyed. The same is true of civilizations. Not one in history has lasted forever: Why should ours be an exception? ... We don’t depend on gold, like the Roman Empire…But we do depend on critical nodes that make up a vast network: the energy production system, the financial system, the climate system, and many more. If any one of these subsystems defaults, it could send out reverberations that generate a cascade of failures, bringing the whole system down. We’ve seen ominous shocks just in the last century: the world wars, the Great Depression, the 1973 oil crisis, the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic. What will be the next shock? When it arrives, our civilization could quickly become just another paragraph in future history books. And if something goes really wrong with the Earth’s climate [note from Ciaran: such as a nuclear winter which causes a new ice age]—well, there may not be anyone left to read them.”

Coincidentally, while I was writing this essay series, Aris Roussinos published a piece for Unherd which touched on similar sentiments to my own but from an Anglophonic angle. In It’s time for Anglofuturism, he writes:

“As the Marxist thinker Wolfgang Streeck warns: “We are facing a long period of systemic disintegration, in which social structures become unstable and unreliable, and therefore uninstructive for those living in them…” It is a time, perhaps lasting centuries, when “deep changes will occur, rapidly and continuously, but they will be unpredictable and in any case ungovernable”. Life in such a society “offers rich opportunities to oligarchs and warlords while imposing uncertainty and insecurity on all others, in some ways like the long interregnum that began in the fifth century CE and is now called the Dark Age”.”

A new “Dark Age.” The optimistic part of me would very much like to think this is hyperbolic. However, at a time of dreadfully mismanaged plague, a hot war on the edge of Europe occurring alongside rising tensions with China that both risk summoning the nuclear demon, absurd infighting within the West over matters as demonstrably simple as the reality of biological sex differences, the normalization of totalitarianism dressed up as compassion in the form of politically correct censorship and ‘cancellation’ designed to crush resistance to Diversity-Inclusion-Equity dogma, and shockingly high rates of addiction and suicide, the West may well be closer to a new Dark Age than we’d like to acknowledge. Derek Mahon may have had a similar inkling:

The new dark ages have been fiercely lit

to banish shadow and the difficult spirit

And on these inklings by one of Ireland’s great word smiths, Dan Hitchens of First Things writes:

“Mahon complains of Ireland’s surrender to “the post-Cold War, global-warming age / of corporate rule, McPeace and Mickey Mao,” abandoning its traditions of dissent, anarchic humor, and spiritual resistance.”

Yet if a new Dark Age is coming, or already upon us, what can Ireland actually do about it? “Are we not”, as queried in Part 1, “a rudderless and floundering plaything of globalist ruling classes who ensure we obey like good little Paddies?” A puppet with the strangely convergent five fingered hand of the Rulers up its backside? In some ways, we undoubtedly are. Chief political editor at Spiked, Brendan O’Neill, would seemingly agree. O’Neill recently provided some illustrations of such a view when writing about punitive EU resistance to Ireland utilizing its own peat resources for energy, despite the double barrel dangers of war and economic turmoil looming large this winter:

“Let’s be plain about it: a nation that cannot control its own soil is not a free nation. If there is an external power that can threaten and discipline you over what you do with your own terra firma, then you are a nation in name only…And it isn’t only on the issue of peat. From the EU’s challenges to aspects of Ireland’s tax system to its dispatching of the ‘Troika’ of powers in 2010 to reprimand the Irish government for its economic errors, almost every element of political decision-making in Ireland is now shaped by EU interference. Ireland’s soil, its right to set taxes, its economic governance, its borders – all are arrogantly interfered with by commissioners no one in Ireland voted for.”

That said, perhaps we could aspire toward regaining some of the “dissent, anarchic humor, and spiritual resistance” pointed to by Hitchens above? Perhaps we could at least attempt to reclaim some control over our future? We may not be able to change the world, but we can try to change ourselves. Maybe if we do some things right, other countries will notice and follow suit. And even if we make mistakes in our attempt at greater autonomy, others may learn from them and avoid repeating the same errors.

With all this in mind alongside the themes discussed in Part 1, I’ll focus on three core areas in which Ireland can lead by example: energy security, food sovereignty, and epistemic safeguarding. The rest of this essay will explore energy. Samhain is upon us, and Winter is coming.

**********

In a Forbes piece about Europe’s perplexing dependence on Russian fossil fuels, Ariel Cohen writes:

“The energy crisis unfolding in Europe has many drivers, but EU green policy hubris, and Russian hard-nosed energy poker are the key. The main lesson is: one cannot will energy transformation into reality without building ample, reliable and economically viable baseline generation capacity.”

While reading as if this was written yesterday, Forbes published this piece by Cohen in October 2021. Four months before Putin invaded Ukraine. Our dependence on Russian’s energy exports were, you see, an issue long before the war. (As such, one cannot but consider that this asymmetrical lever of power perhaps emboldened Putin into sending in his troops in February?)

Earlier in the piece, Cohen points to the seemingly detached dreamworld that EU decision makers have been living in. A dreamworld which involved placing huge emphasis on decarbonising Europe, without actually building commensurate energy replacements:

“As the EU sought to decarbonize their energy infrastructure, Brussels failed to establish a reliable baseline capacity for electricity generation. Today, without the ample nuclear, coal, and gas power stations, Europe would be a dark and cold place indeed. Moreover, they lack sources of energy for low renewable periods like the “windless summer” of this past year in the UK. Low wind speeds and cloud cover are becoming more unpredictable as climate change progresses, and the lack of baseload generation has resulted in the current crisis.”

As mentioned in Part 1, the Germans in particular have been impacted by this mess because of their insane voluntary dependence on Russian energy. “The entire German system, it turns out, depended on a never-ending supply of cheap Russian gas.” When Jeremy Stern wrote that for Tablet Magazine, he wasn’t much exaggerating. In a recent piece for Spiked, Ralph Schoellhammer of Webster University Vienna describes how “An eco-obsessed elite has sacrificed energy and food security to the climate agenda.” Of particular note, is that the Rulers of Europe have voluntarily created a situation in which the real poor of today will go hungry in the cold for the sake of the hypothetical poor of the future; a hypothetical future poor who might be negatively affected be affected by increased global temperatures. This is not an exaggeration. Schoellhammer quotes Cem Özdemir, the German food and agriculture minister, as saying that “‘hunger should not be abused as an argument to make compromises regarding biodiversity or protection of the climate’.” Shoellhammer unpacks this supremely archetypal representation of the Rulers’ mentality in relation to human life as follows:

“Here Özdemir effectively dismissed people’s concerns about food production as nothing more than an attempt to undermine his government’s environmental plans. And so now the German government, sticking rigidly to the green agenda, is doubling down on its suicidal policies.”

Will Minister Özdemir go hungry or without heating this winter? Barring the total collapse of German society into gritty anarchy—which is all too easy to imagine in the event of nuclear war, for instance—he almost certainly won’t. Hunger and cold are problems for the unwashed plebs, not for the Rulers. “For green ideologues”, Schoellhammer writes, “hardship is a price ordinary people are expected to pay.” Thomas Fazi painted a similar picture for the UK as well as Germany in a recent piece for Unherd:

“In the UK, 45 million people are forecast to face fuel poverty by January 2023; as a result, “millions of children’s development will be blighted” with lung damage, toxic stress and deepening educational inequalities, as children struggle to keep up with school work in freezing homes. Lives will be lost, experts warn. Meanwhile, in Germany’s Rheingau-Taunus district, the authorities have carried out a simulation of what such a blackout would mean for them, and the results are shocking: more than 400 people would die in the first 96 hours. And this in a district of just 190,000 inhabitants.”

As we can recall from the proposed moose genocide in Part 1, dogmatic and myopic green ideology is quite the driver of absurd behaviour. Mary Harrington provides a few examples in a piece for Unherd:

“Nothing produces true believers today quite like the environmental movement. Gluing yourself to London or pouring soup over a priceless painting is all in a day’s work. For your green stunt to stand out, you need to do something eye-catchingly disgusting such as pouring human faeces over a statue of Captain Tom.”

Environmentalist and author Michael Shellenberger—whose book Apocalypse Never will be discussed below—recently listed a few more examples of what these “true believers” get up to in the service of their ideology:

“Dumping milk onto floors. Hurling food onto walls. Refusing to eat. Gluing body parts. Throwing paint. Refusing to leave. Threatening to pee and poop in your pants. Screaming accusations. Are those the behaviors of a toddler’s temper tantrum? Yes. But they’re also the dominant tactics of today’s climate activists.”

Yet how could Germany, a country so widely known for its cool rationality and ruthless efficiency, fall prey to a naïve green ideology that has left it hostage to the whims of Putin’s kleptocracy? Privileged restlessness and Nazi guilt, suggests Schollhammer in another piece for Spiked entitled Green ideology has brought Germany to its knees:

“More than anywhere else, the green movement truly took off in Germany. Driven by a combination of bourgeois boredom and a sense of guilt for the crimes of the Second World War, Germany’s green movement turned against modern technological society. It was especially hostile towards industrial energy production.”

And a major exemplar of industrial energy production, of course, is that of nuclear. According to Schollhammer, there “are still three nuclear power plants operating in Germany today.” These were built in the 1960s and 1970s and at the time of writing in August, were “due to be phased out by the end of this year.” It seems as of recent weeks, however, that the Rulers in Germany have decided to keep their three remaining plants online until April. They have also been ramping up coal power, a massive pollutant.

**********

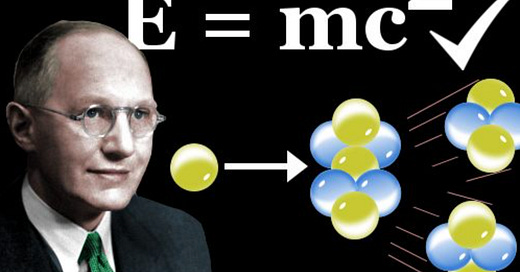

What may come as a surprise to the reader who grew up watching the Bart and Lisa pulling three eyed fish out of rivers, or remember the great fuss around the Chernobyl or Fukashima disasters, is that nuclear power may have been the safest, cheapest, and most environmentally friendly solution to Europe’s energy needs for quite some time. In his book Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All, the aforementioned Michael Shellenberger writes:

“Nuclear is thus the safest way to make reliable energy. In fact, nuclear has saved more than two million lived to date by preventing the deadly air pollution that shortens the lives of seven million people per year…A study published in late 2019 found that Germany’s nuclear phase out is costing its citizens $12 billion per year, with more than 70 percent of the cost resulting from 1,100 excess deaths from “local air pollution emitted by the coal-fired power plants operating in place of the shutdown nuclear plants.” (pg. 151)

He then offers a comparison between France and Germany that is very timely given the situations both countries find themselves facing over the coming months and years:

“With France and Germany, we can compare two major (sixth and fourth) economies, which are highly proximate geographically and at similarly high levels of economic development, on a decades long timescale. France spends a little more than half as much for electricity that produces one-tenth of the carbon emissions of German electricity. The difference is that Germany is phasing out nuclear and phasing in renewables, while France is keeping most of its nuclear plants online.” (pg. 151)

In this myth busting and thought-provoking book, Shellenberger diligently traces the reputational rise and fall of nuclear power amongst environmental activists and the wider public, and how the anti-nuclear movement is driven more from a place of ideological commitment than scientific rationale around the benefits and downsides of the technology. “Only nuclear,” he plainly states, “not solar and wind, can provide abundant, reliable, and inexpensive heat.” (pg. 153) Apart from the obvious fact that cloudy or windless days are obstacles to solar or wind, whereas nuclear provides a steady flow, there is a huge cost discrepancy too. “Between 1965 and 2018,” Shellenberger writes, “the world spent about $2 trillion for nuclear and $2.3 trillion for solar and wind.” By the end of this natural experiment, however, “the world received about twice as much electricity from nuclear as it did from solar and wind.” (pg. 152)

As a related aside, the poor cost effectiveness of current renewables has not gone unnoticed by those in charge of countries with smaller budgets and more direct skin in the game. In a piece for Spiked about John Kerry’s September mission to Africa, Professor at London South Bank University, John Woodhuysen, writes:

“John Kerry, Joe Biden’s special presidential envoy for climate, was in Dakar, Senegal last week. He was there to tell a conference of Africa’s environment ministers how they should run their countries. His main message was that African countries should give up all hope of using natural gas to grow their economies…Indeed, Kerry’s jaunt was only the latest chapter in the long story of Western eco-imperialism. The West’s insistence that Africa forgo the gas, oil and coal at its disposal has long been a blockage on Africa’s capacity to industrialise…Today, more than 600million Africans have no access to electricity at all. So it is no wonder that Macky Sall, president of Senegal and chair of the African Union, has rejected Kerry’s orders: ‘You cannot tell us that renewables alone can develop a continent – it has never been the case anywhere else and it cannot be the case in Africa.’”

Apart from the economic impacts, the humanitarian cost of a lack of access to electricity is horrendous. For example, a July 2021 paper by Zhao and colleagues published in the Lancet found that 90% of the more than 5 million deaths per year due to “non-optimal temperatures” were due to cold rather than heat. In a media environment saturated with content about global warming, the fact that 90% of people who die from non-optimal temperatures do so from cold is worth remembering. Moreover, a 2016 WHO report outlined how 4.3 million people die each from household air pollution (HAP)—most of whom women and children—caused by burning dirty fuels like kerosene, manure, and coal in traditional stoves and open fires with poor ventilation. They must do this “because they lack access to clean, affordable, convenient alternatives such as electricity, gas, biogas and other low-emission fuels and devices.” With a larger death toll than “malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS combined…HAP is the single most important environmental health risk factor worldwide, more important even than lack of access to clean water and sanitation. These terrible distinctions make HAP perhaps the most overlooked, widespread health risk of our time.” To put these awful annual death tolls of 5 and 4.3 million people respectively into perspective, total global Covid deaths in the nearly 3 years since Jan 2020 (at the time of writing in Oct 2022) are listed as less than 6.6 million.

This slight digression was to illustrate that the world needs more energy, not less. And to secure this, we need clean sources of energy that do not simply work when it is windy or sunny enough. African leaders who were subjected to John Kerry’s anti-fossil fuel sermon understood this. This brings us back to nuclear.

But what about nuclear waste? Will there not be simpleton Homer Simpson like nitwits left dangerously disposing huge numbers of buckets of glowing green goo that will harm people? On this, Shellenberger states that “nuclear waste…is the best and safest kind of waste produced from electricity production. It has never hurt anyone and there is no reason to think it ever will.” (pg. 152) He goes on to write that “One of the best features of nuclear waste is that there is so little of it. All of the used nuclear fuel ever generated in the United States can fit on a single football field stacked less than seventy feet high.” (pg. 152)

**********

Thankfully, there are at least some Irish journalists writing about this topic. In an early February 2022 piece for the Irish Examiner about Ireland’s possible transition to nuclear energy, Mick Clifford writes of Ireland’s 1978 protests in opposition “to a form of energy that was central to an arms race between two superpowers intent on propelling us all off to hell in a handcart”. Clifford describes how the protests succeeded and “nuclear energy was banished and subsequently banned.” And then, in a sentence I am sure he has had a darkly wry chuckle about since given how events unfolded soon after, he writes: “Roll it on 40-plus years and the existential threat is no longer itchy fingers in the Kremlin and Washington, but the enveloping doom of climate change. Wherefore nuclear now?” Little could Mick have known, of course, what Vlad had up his sleeve for Ukraine on February 24th of that same month, or the nuclear weapon sabre rattling he carried out after Russia met much more stern resistance than expected. Clifford then concludes that, given the relevant experts and sources in his piece, “there won’t be any new nuclear plants in this country for the foreseeable future”. However, he acknowledges that it is “not easy these days to see too far into the future.” Too right Mick!

And so, given how the cookie has crumbled since Putin’s invasion, it would seem that an urgent and level headed revisiting of the 1999 Electricity Regulation Act that had banned electricity produced by nuclear fission here in Ireland is due. The Irish organization 18 For 0 has been advocating for this:

“Nuclear power is an extremely low carbon form of reliable electricity generation and is the cornerstone of many countries' decarbonization strategies. Ireland currently has two statutory bans on nuclear power and is not being considered by the Irish Government for its potential role in our clean energy future. We aim to present the environmental and economic case for modern nuclear energy to all key stakeholders and to outline Ireland’s capability to operate a robust nuclear power programme.”

Dr Paul Dean of the School of Engineering at University College Cork has previously described, in an April 2020 piece, how the Irish “power system is too small for a conventional large nuclear plant” of our own, but that the new Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) being developed, if viable, might make good sense alongside traditional fossil fuel plants as back-ups to wind and solar in order “to make sure our energy system is secure and reliable.” While Deane is supportive of nuclear energy in theory, he still remains soberly realistic:

“On the balance of evidence, the odds are stacked against nuclear power in Ireland. The technical challenges are large but maybe secondary to the public acceptance concerns. But climate change is a serious problem and we need to be looking at lots of solutions to stop it…even the ones we may not like. For Ireland, this means that if there is a breakthrough in nuclear technology, we should at least talk about it.”

On such possible breakthroughs, Joanne Liao writes in a November 2021 piece for the International Atomic Energy Agency:

“Given their smaller footprint, SMRs can be sited on locations not suitable for larger nuclear power plants…Both public and private institutions are actively participating in efforts to bring SMR technology to fruition within this decade. Russia’s Akademik Lomonosov, the world’s first floating nuclear power plant that began commercial operation in May 2020, is producing energy from two 35 MW(e) SMRs. Other SMRs are under construction or in the licensing stage in Argentina, Canada, China, Russia, South Korea and the United States of America. More than 70 commercial SMR designs being developed around the world target varied outputs and different applications, such as electricity, hybrid energy systems, heating, water desalinisation and steam for industrial applications. Though SMRs have lower upfront capital cost per unit, their economic competitiveness is still to be proven in practice once they are deployed.”

William Reville, emeritus professor of biochemistry at University College Cork, has also written in support of nuclear energy and has highlighted the newest innovations in SMRs. In a piece for the Irish Times from October 6th of this year, he writes:

“Recent developments in the nuclear power industry allow [SMRs] to be mass-produced at relatively low cost and deployed quickly and safely, making the nuclear option more attractive. The American Nuclear Regulatory Commission recently certified the SMR for use…Starting up nuclear power in Ireland would greatly help us to meet our greenhouse gas emission targets. In the absence of nuclear power we will depend on burning gas, mostly imported, to generate electricity to supplement wind and solar for the next 30 years. Nuclear power could save our bacon but if we delay much longer, even that option will be too late to bail us out.”

With regards to seriously talking about it, however, things are not looking so promising. According to recent reporting by James Wilson at Newstalk: “My own view and the view of the Government is that the future for Ireland is renewable energy,” said Minister for Public Expenditure Michael McGrath. “It’s not nuclear.” This is despite the fact that John Powers, President of Engineers Ireland, has clearly stated that “the construction of nuclear power plants is very well regulated [and] they’re very, very safe.” “However,” writes Wilson, “whether or not a power plant is built in Ireland, many Irish homes will soon be powered by nuclear power regardless.” This is because:

“In the spring, An Bord Pleanála gave permission for construction to begin on the subsea Celtic Interconnector that will bring electricity from the French Republic to Ireland; France generates roughly 70% of its energy from a fleet of nuclear reactors and President Emmanuel Macron has promised to build 14 more.”

A “subsea Celtic Interconnector”? Sounds like something that could be turned off on France’s side if things got bad enough on the mainland. Or mysteriously blown up like we recently saw with the Nordstream pipeline. Would many small plants of our own not provide greater energy security?

Over the short term though, we will not have nuclear plants of our own regardless of their viability or public support as they may take some time to build even if we decide to take “the nuclear option”, as Professor Reville described it. As such, we must acknowledge that we have peat resources of our own on which we can use if energy is scarce, as well as address the fact that natural gas—the cleanest fossil fuel by a country mile—is in short supply and that this must be addressed. Unfortunately, Ireland is “the worst prepared country in Europe at this point in time” according to Don Moore, Chair of the Energy and Climate Action Committee at the Irish Academy of Engineering, and that “we’ve got ourselves into this situation” by choosing not to have any gas storage in the bank for a rainy day. Furthermore, while “experts believe that there are billions of barrels of gas off Ireland’s coasts”, writes Niamh Ui Bhrian in a piece for Gript.ie from August, “we are telling them that our green reputation matters more than our ability to ensure our people can access energy.” Ui Bhrian elaborates:

“Last year, the government delightedly announced that it would refuse any more licenses to find oil or gas in Ireland, even though the rest of the world is hastily revisiting all those promises to ‘leave fossil fuels in the ground’…“Through the Climate Act 2021, Ireland has closed the door on new exploration activities for oil and gas. There is no longer a legal basis for granting new licences,” Eamon Ryan trumpeted, with the usual addendum that Ireland was ‘leading the way’ on ending fossil fuel use…He might, if he bothered to examine the situation a little more closely, have seen that we are leading the way because other countries are understandably backing away from a ruinous strategy which pretends that renewable energy isn’t unreliable and is blind to what will happen when energy supplies are closed off without dependable alternatives.”

The virtue signalling Rulers of our nearest neighbours have walked themselves into a similar sort of mess. On the situation in the UK, Anonymous Banker recently wrote the following for Konstantin Kisin’s Substack:

"G7 obsession with blocking fossil fuel investment and other interventions in our energy markets for political ends have caused problems that would have reared their head without the actions of Putin. Successive governments sought to flex their green credentials in their 5 year terms, hoping that clean energy would be on stream by the time it was needed. They didn’t stop to ask what would we do if it wasn’t? This is not an argument about climate change or in favour of fossil fuels – it’s simply pointing out that we leapt out of the plane hoping the parachute would be ready before we hit the ground. Faced with contractions in supply, there is only one outcome – higher prices. We chose to restrict capacity and are now paying the price."

Aris Roussinos offers indications of his own Anglofuturist vision for Britain as one “where every county town has its own Small Modular Reactor providing clean, abundant nuclear energy” and where “small family farms … provide the country’s food security.” This is obviously in rough alignment with my own suggestions for Ireland thus far. Though what Roussinos doesn’t elaborate upon in his piece, is the types of agriculture that could take place on those farms.

Part 3 soon.